The fact that a story like that of Majorana and Pelizza’s machine has reached the Senate’s table says much more than its technical content: it speaks to the collective need to believe, even today, that knowledge can transcend the limits of possibility.

There comes a moment, in the history of every legend, when the boundary between reality and fiction blurs. It happened yesterday, when the story of Ettore Majorana and his supposed disciple Rolando Pelizza once again filled a room in Palazzo Madama, no longer as a curiosity for enthusiasts, but as the topic of an official meeting.

In the Nassiriya Hall, a panel of diverse speakers—a theologian, a historian, an engineer, the president of a scientific association, and a writer—brought to life the figure of the physicist who died in 1938 and his enigmatic “infinite energy machine.” At the center of the debate was Alfredo Ravelli ‘s book Majorana-Pelizza: The Unveiled Secret , which collects letters, photographs, and testimonies of Majorana’s “second life,” said to have been spent in a monastery in southern Italy to escape the nightmare of the atomic bomb.

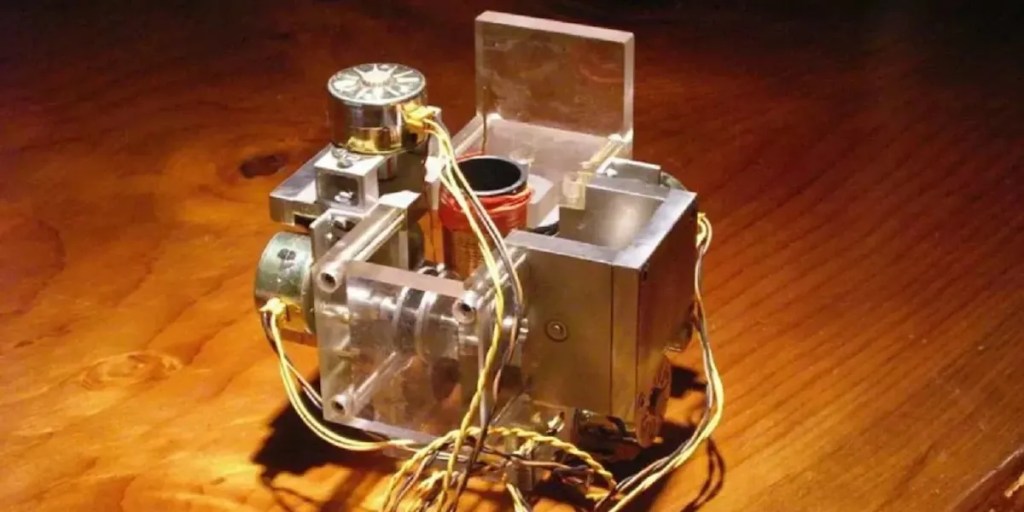

According to the story, Majorana neither died nor fled abroad, but continued his experiments in secret, supported by Rolando Pelizza , a Brescian entrepreneur who claimed to have built, under his guidance, a machine capable of annihilating matter, producing unlimited energy, and even rejuvenating human beings. A vision that, even merely uttering it, slips from the language of physics to that of the Promethean myth.

Ravelli claims to possess thirteen autographed letters from Majorana, photographs, and a film supposedly showing Pelizza alongside an elderly physicist, all “examined and authentic.” He recounts experiments in the transmutation of matter , such as a flame that was supposedly transformed into grain, and a proposal—both symbolic and provocative—to convert hundreds of thousands of religious medals intended for pilgrims into gold.

Then come the most dizzying chapters: an alleged agreement signed by George W. Bush in 2001 to produce gold using the machine, Barack Obama ‘s interest in a secret operation “against crime,” and finally an experiment in which Majorana himself, rejuvenated by the device’s “energy translation,” supposedly returned to the appearance of a thirty-year-old man.

Senate Vice President Gian Marco Centinaio , who granted permission to use the room for the conference, later clarified: “Use of the space does not imply any endorsement of the content presented, nor support for theories lacking scientific foundation.” A diplomatic but unavoidable clarification, which highlights how fine the line is between freedom of research and institutional prudence.

Yet, the fact that such a story has reached Palazzo Madama remains a significant cultural event. It means that the legend of Majorana continues to exert a profound magnetism, capable of drawing believers and skeptics into the same gravitational field. The figure of the vanished genius, the visionary disciple, and the machine capable of solving humanity’s problems compose an irresistible narrative, suspended between scientific faith and the desire for technological redemption.

Lorenzo Paletti, a physicist and illusionist, tackled the same issue in his book, La Macchina di Rolando Pelizza (2024), investigating it methodically and rigorously. His work showed how behind every alleged proof lurked ambiguity, illusion, or misunderstanding. But the fascination remains: every era needs its own mysteries and promises of eternity.

Today, Majorana and Pelizza are no longer just a matter of news: they have become contemporary archetypes . One represents the knowledge that flees so as not to destroy, the other the faith that pursues to transform. And their impossible machine, which annihilates and recreates, is perhaps nothing more than a symbol: the human dream of rewriting the laws of matter and time, where science bows to the longing for God.

–

–